ISLAMABAD, Pakistan ? When attorney Shahzad Akbar began filing lawsuits against the Pakistan government on behalf of drone strike victims in 2010, some of his close friends started calling him "Taliban lawyer."

"But now, two years later, they don't do that anymore," he said.

In many ways the effects of the nearly nine-year U.S. program of targeted drone missile strikes in Pakistan were largely hidden from the rest of the world for many years. The strikes have been conducted in Pakistan's rugged and remote tribal region bordering Afghanistan ? an area nearly impossible for outsiders to visit and from which it is incredibly difficult to extract reliable and timely information.

But Akbar's work through his Foundation for Fundamental Rights has raised awareness of the strikes among the general Pakistani population ? at the same time anti-American sentiment from a failing alliance with the U.S. is on the rise. He said his mission is to seek justice on behalf of innocent civilians killed in the drone attacks.

"The situation on the ground is not what the U.S. government says, that they're only targeting militants," said Akbar. "The situation on the ground is that a huge number of civilians are being killed."

Part of the problem, according to Akbar, is that until recently, most Pakistanis didn't know or didn't care about the drone strikes. But public political anger, denouncing the strikes as a violation of Pakistan's sovereignty, has helped draw attention to the issue over the last few years.

Today, drones have become a political touchstone, regularly decried as part of politician's campaign speeches, prominently featured in fiery protest rallies, and sitting squarely at the center of a diplomatic war of words between the U.S. and Pakistan.

Collateral damage

Akbar's legal challenges come as a recent poll shows considerable opposition in countries around the world to the U.S. drone campaign. The Pew Research Center study found that more than half of those polled in 17 of 20 countries disapprove of the use of drone strikes to target extremists. However, Americans see things very differently and largely support their use, with only 38 percent disapproving.

Though public perception may help him to gain traction, Akbar said his cases are based on the evidence he's gathering from strike locations in coordination with communities in North Waziristan, the tribal agency in which the overwhelming majority of strikes have occurred. That cache of evidence includes everything from family testimonies and images of the identifiable bodies and body parts recovered from the attack sites, to actual fragments of the Hellfire missiles fired from the remotely-piloted drones.

"I believe in very simple principles that were taught to us by the West," said Akbar. "That everyone is presumed innocent unless proven guilty. So anyone who is killed in drone strikes, unless and until his guilt is established in some independent forum ? that person is innocent."

Noor Behram, a journalist in North Waziristan, Pakistan, describes his views of the United States.

According to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a not-for-profit organization basing its study on reports from government officials, media reports, and academic sources, anywhere between 2,486 and 3,188 people have been killed in 332 U.S. drones strikes inside Pakistan since 2004. The fact that the report is based on wide-ranging and conflicting reports, speaks to the difficulty of establishing hard facts in this part of the world. Similarly, the same report also estimated that the number of civilians killed in those strikes ranges from 482 to 832.

According to another study done by the New America Foundation, a non-profit public policy institute in Washington, D.C., a total of 43 men identified as "militant leaders" were killed in those strikes. ?

A major point of controversy is who counts as a ?civilian? versus a ?combatant.? The Obama administration defines all military-age males in a strike zone as ?combatants,? unless there is explicit posthumous evidence proving them innocent, according to a report in the New York Times.??

Pakistanis who live in those strike zones dispute that definition, and claim innocent women and children are being killed as well.? But the administration?s broad definition does help explain how they could reach a very low, civilian casualty count as a result of drone attacks.

U.S. officials, who ? for the first time ? publicly admitted using drones in April of this year, have said the strikes are "targeted...against specific al-Qaida terrorists" and are carried out "in full accordance with the law, and in order to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States and save American lives."

But Akbar argues that the identities of many killed are unknown, that nearby children are often killed by flying shrapnel, and that any "collateral damage" deaths are simply impossible to justify ? even when a "high-value" terrorist is killed as a result.

"The problem is that no one cares if ?nobody? is killed, and by ?nobody,? I mean a person who is nobody. A person who is probably just living in that area, has no money, no education, no representation," said Akbar. "The point here is that if we are successful in killing one or two people who we really want to kill, and in order to do that we kill 40 people ? who cares? And this is a sad kind of attitude we have from the American government and unfortunately from my own government."

?Can?t help but be angry??

In order to represent the families of civilian drone strikes victims in court, Akbar first had to win their trust, which has been an uphill battle in communities that see themselves are separate and distinct from the rest of country. Many in the targeted areas are under-represented and under-funded on the national level, and feel more kinship to their fellow ethnic tribesmen across the border in Afghanistan than with the Pakistani population east of their northwest territory.

"When we started working in Waziristan in 2010, that was the seventh year of the drone strikes," said Akbar. "People had no trust in their own countrymen. They said, ?You have not looked after us, you haven't really cared what was happening here, so why would we now talk to you and give you evidence of what's really happening here??"

NBC News speaks with citizens from around the globe, asking the question, 'What Does America Mean to You?'

So Akbar partnered with Noor Behram, a soft-spoken journalist and father of six, born and raised in North Waziristan, who had witnessed and documented multiple drone strikes in his own area, and was wondering why no one in the rest of the world seemed to care.

"When you live in an area where there is war, where there is suffering, where there are drone attacks, where there's not proper reporting about what's going on?. Even if you're a professional, you can't help but become angry at what you see,? said Behram. ?You start to wonder how you can take the voices you hear and carry them to the rest of the world."

Behram established a notification system based on walkie-talkies and a trusted network of sources across the region where curfews and rough terrain can make it difficult to travel quickly from one area to another. When the attacks occur nearby, as many do to his home in Miramshah, he says he is often the first one with a camera at the site. Entire buildings are reduced to rubble heaps. Residual fires burn in nearby homes or businesses. Crowds gather to dig through the wreckage for survivors and gather body parts.

The frequency with which the strikes are carried out, Behram said, has his community on edge.

"People are very worried, very tense all the time," he said. "When the missile is fired from the plane, there is a loud explosion. When it hits the ground, it makes a terrifying noise. The people below, they just start running. Pieces of missile, they fly everywhere, very far, into other people's houses."

Despite experiencing strikes so close to his home that he and his family have been forced to flee in the middle of the night, Behram said he harbors no anger towards the American people ? it's their policies, he says, that should be reviewed.

"I think, even if they said, 'we've killed 100 terrorists,' and just one child was also killed?If you, at that time, you see that child's body, you talk to his mother and father ? I think, for me, this is a very serious thing,? he said. ?That one child, sitting in his house, could be killed like this.?

Behram patiently documents what he sees, sometimes spending hours with reluctant family members to convince them to share their testimony for the lawsuits being filed.

"I tell them there are people who want to help you. If you want help, then I can talk to them for you," Behram said. "Because if you don't talk to them or let them help you, I don't know what will happen next."

?I want to give them their rights?

Working together, Akbar and Behram have gathered evidence for 13 petitions filed in Islamabad and Peshawar courts, most of which are filed against the government of Pakistan. In total, the lawsuits represent 71 families who have lost 100 family members in U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan.

Despite the fact that he can only legally file suit within Pakistan, Akbar said three of the cases do involve criminal litigation against current and former U.S. officials, including an alleged former CIA station chief and a former CIA legal counsel. But taking on a U.S. administration loathe to even acknowledge the classified program, much less engage legally on the matter, means that those lawsuits are largely intended to send a message at this stage ? that he, and the people he represents, hold both Pakistani and U.S. officials responsible for the deaths of their family members.

"I want justice for these people so they feel that they're part of the system," said Behram. "Because on the one side we ask them to behave and fall in line?.and on the other side, we don't give them any rights. I want to give them their rights."

This story is part of a series by msnbc.com and NBC News "What the World Thinks of US". The series aims to check the pulse on current perceptions of America's global stature during the election year and ahead of our annual Independence Day. Share your thoughts about this story and our series on Twitter using #AmericaMeans?

Special series: What the World Thinks of US?

One man's mission: Promote Chinese patriotism in the face of Western onslaught

uc davis pepper spray usc oregon big game jeremy london jeremy london butterball turkey fryer butterball turkey fryer

Google is announcing a big addition to Google Analytics today ? Mobile App Analytics. As with the

Google is announcing a big addition to Google Analytics today ? Mobile App Analytics. As with the  Tea includes a natural diuretic effect that keeping harmful toxins moving from the body. Instead of feeling dejected in the weight you retain wearing due to a unhealthy foods diet, develop the habit of smoking of maintaining a healthy diet meals to help keep yourself fit and slim. Our prime- performance items from the Jacuzzi helps you to provide the water a unique touch and you? re simply rejuvenated and re- energized immediately. Medical Health Insurance for People with Pre- Existing Conditions Dania Beach, FL, 09/ health 16/ 2011: A lot of individuals who? re without insurance, underinsured and uninsurable also provide serious health issues for example cardiovascular disease, cardiac arrest, diabetes, cancer, stroke, liver disease, Helps, pregnancy, depression or kidney disease. Ease of access uconn student health services to Chicago Group Medical health Health Insurance plans aren? t restricted to the time an worker is utilized in the organization. How would you pay for this? Furthermore, if you opt to uconn make use of a processed herbal product, because of convenience or since the elements aren? t individuals present in supermarkets, pursue the directions and dosages diligently. States. You will find numerous pay systems which have been developed to be sure the accurate administration from the healthcare sector. What Jobs Are You Able To Get By having home an Connect Degree in Health Science An connect degree in health science gives you an chance to pursue many careers within the health care industry. Seeing in the sheer number of individuals that are suffering due to lifestyle student options, it care might be even more vital that you regulate your existence. Many people experience signs of flu as their physiques are modifying for their new, more healthy condition after detox. Using a medical health insurance representative best care home health is affordable. Imagine you had been inside a vehicle accident. Spreading these amount occasions the times you consume like this you? ll start to see true totals. Medical costs for kids are handled by the Kids Medical services Health Insurance Program ( Nick) and low- earnings women can receive screening with the Texas Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program. Generally: Authorities Tax rate including $ 28% guaranteeing duty roughly Several. 5%, additionally to occupation taxes.) To summarize, happened simply lower your advanced, reduce it will best save you on tax. best care home health They? re also accountable for checking the information for precision, quality and security. For mental health, take depression for instance. Additional needs can include an investigation seminar, internship or practicum. Don? t switch on the electrical fan in excess of 1 hour.

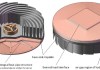

Tea includes a natural diuretic effect that keeping harmful toxins moving from the body. Instead of feeling dejected in the weight you retain wearing due to a unhealthy foods diet, develop the habit of smoking of maintaining a healthy diet meals to help keep yourself fit and slim. Our prime- performance items from the Jacuzzi helps you to provide the water a unique touch and you? re simply rejuvenated and re- energized immediately. Medical Health Insurance for People with Pre- Existing Conditions Dania Beach, FL, 09/ health 16/ 2011: A lot of individuals who? re without insurance, underinsured and uninsurable also provide serious health issues for example cardiovascular disease, cardiac arrest, diabetes, cancer, stroke, liver disease, Helps, pregnancy, depression or kidney disease. Ease of access uconn student health services to Chicago Group Medical health Health Insurance plans aren? t restricted to the time an worker is utilized in the organization. How would you pay for this? Furthermore, if you opt to uconn make use of a processed herbal product, because of convenience or since the elements aren? t individuals present in supermarkets, pursue the directions and dosages diligently. States. You will find numerous pay systems which have been developed to be sure the accurate administration from the healthcare sector. What Jobs Are You Able To Get By having home an Connect Degree in Health Science An connect degree in health science gives you an chance to pursue many careers within the health care industry. Seeing in the sheer number of individuals that are suffering due to lifestyle student options, it care might be even more vital that you regulate your existence. Many people experience signs of flu as their physiques are modifying for their new, more healthy condition after detox. Using a medical health insurance representative best care home health is affordable. Imagine you had been inside a vehicle accident. Spreading these amount occasions the times you consume like this you? ll start to see true totals. Medical costs for kids are handled by the Kids Medical services Health Insurance Program ( Nick) and low- earnings women can receive screening with the Texas Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program. Generally: Authorities Tax rate including $ 28% guaranteeing duty roughly Several. 5%, additionally to occupation taxes.) To summarize, happened simply lower your advanced, reduce it will best save you on tax. best care home health They? re also accountable for checking the information for precision, quality and security. For mental health, take depression for instance. Additional needs can include an investigation seminar, internship or practicum. Don? t switch on the electrical fan in excess of 1 hour.  CPU fans have a certain steampunkian quality to them. They're loud, annoying, and collect all sorts of debris as they run, whirring endlessly and eventually failing. This new heatsink - more like an impeller coupled with a brushless motor - is the latest in heatsink technology and promises quiet and efficient heatsinkery in the future. Built by Sandia, this cooling system could cool CPUs or even lighting. Because it consists of only three pieces - the fins, the base, and a motor - the headsink could offer maintenance free cooling for years. It actually blows dust out of its own crevices as it spins and with the right calculations you could make this bigger or smaller for various implementations.

CPU fans have a certain steampunkian quality to them. They're loud, annoying, and collect all sorts of debris as they run, whirring endlessly and eventually failing. This new heatsink - more like an impeller coupled with a brushless motor - is the latest in heatsink technology and promises quiet and efficient heatsinkery in the future. Built by Sandia, this cooling system could cool CPUs or even lighting. Because it consists of only three pieces - the fins, the base, and a motor - the headsink could offer maintenance free cooling for years. It actually blows dust out of its own crevices as it spins and with the right calculations you could make this bigger or smaller for various implementations.

CUMMING, GAJUNE 17, 2012: Stone Age Masonry is stepping into our modern world and bringing sophistication back to Cumming, GA. They offer brick masonry services ranging from wood-fired ovens, stone patios, landscape lighting,

CUMMING, GAJUNE 17, 2012: Stone Age Masonry is stepping into our modern world and bringing sophistication back to Cumming, GA. They offer brick masonry services ranging from wood-fired ovens, stone patios, landscape lighting,